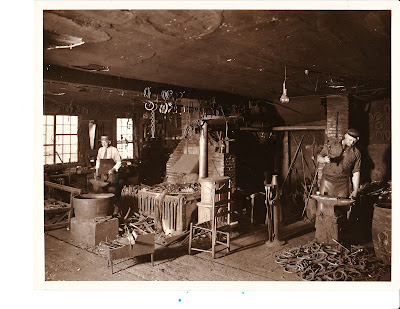

TWO-MAN SMITHY. This 1919 photo shows Warren Davis (left) and George Jewell working in Davis' blacksmith shop near the falls in Bradford. Davis began his 50-plus year career in 1886. Jewell later set up his own blacksmith shop in East Corinth specializing in horseshoeing. Davis later sold an adjoining lot to an automobile dealership at a time when automobiles were greatly reducing the need for blacksmiths. (Bradford Historical Society)

At noon on Wednesday, January 31, 1951, eight Bradford women lost their jobs.

At locations throughout the valley, local telephone

operators were replaced by the automated dial system in the 1950s. They were “uncrowned

heroes of patience, gentleness, and courtesy.”

Gone was the “human

aspect of a mutual friend,” who often knew which store you wanted when you

asked for “the grocery store.” Gone was

the original 911, whose quick thinking assisted in the face of a fire or other

emergency. Gone was the valuable source of local information and perhaps a bit

of local gossip.

Their positions were lost forever to technology.

This column describes other local occupations lost to technological

change. Many of them were vital to the

community’s daily life before passing into scarcity, obscurity or complete

oblivion. Some disappeared in the 19th or 20th century, while others

are still disappearing today.

Local wagon and

carriage makers were essential in the 19th century. Carriage-making reached the height of its

development at the end of that century and then declined rapidly. By 1915, automobiles outnumbered horse and

buggies nationwide, although horse-drawn vehicles could still be seen on local

roads.

Most area towns had at least one wagon maker. Beginning in

the late 1880s, Julius March of Newbury achieved fame throughout Vermont and

New Hampshire. It was said that he

“worked painstakingly making and repairing carriages etc.” When the demand for carriages declined, he

turned to cabinet-making.

Carlos Bagley of Bradford “was considered second to none in

the state.” He moved to Bradford from Piermont in 1881 and began almost 50

years of producing carriages, sleighs, and farm and express wagons at a mill on

South Main Street.

The prevalence of horse-power created related businesses

such as blacksmithing, wheelwrights, harness makers, and operators of livery

stables.

The blacksmith was an essential craftsman in local

communities. Before the Industrial Revolution, they were the sole manufacturers

of metal tools. Locally, they continued

to make or repair tools, wheels, hinges, and other iron items. Farriers

specialized in producing iron shoes for horses or oxen.

In 1886, there were

nine blacksmiths in Haverhill, four in Orford and three in Piermont. The 1888

Orange County Gazetteer lists twelve in Corinth, eight in Newbury and six in

Bradford.

Fran Hutton was one of the many Corinth blacksmiths. He

lived in Corinth for 50 years, during which he operated a shop. In 1900, he was

listed as a wheelwright as well. In 1909, there was enough of a demand for his

services that he made an addition to his shop.

The decline in the number of horses and the mass-production

of tools significantly reduced the needs for local blacksmiths.

Before the 20th

century, most items were stored in wooden containers. A skilled cooper was a

valued craftsman in each community. Jeremiah Ingalls, who came to Newbury in

1787, was “a cooper by trade and singing master by profession.” In 1871, it was

reported that 94-year old Abner Palmer of North Haverhill had worked at the

cooper trade until over 90 years old and was still able.

In the 19th century, small woodenware shops and factories

replaced single part-time workers. Page’s Box Shop in East Corinth, Proctor

Brothers’ stave factory in Bradford village, Henry Hood’s wooden tub shop in

Topsham, and Stone & Wood Company’s box mill in Woodsville are all examples

of woodware production. Many items once produced by these manufacturers are

still in use but made from other materials.

During the 19th century, many small tanneries existed in the

area. The months-long process by which

workers transferred hides into leather was labor-intensive, exhausting and

dangerous. The mills were filled with noxious odors and the wastewater was

toxic.

As early as 1789, Oliver Hardy of Bradford and later his son

George had a tannery in Bradford village. In 1869, J. & T.P Currier had a

tannery in Haverhill.

Tanneries used the tannin produced by bark mills to process

leather. In 1850, there were 126 bark

mills in Vermont. Until the 1880s, bark mills processed bark, roots, and

branches into a fine powder known as tanbark.

Millwork was extremely dangerous. In the early 1840s, Frank

B. Palmer’s leg was caught in the machinery of a Bradford bark mill. He was taken to Haverhill where Dr. Anson

Brackett amputated the limb.

Palmer’s loss had profound consequences to 19th

century prosthetics. In 1846, Palmer patented a new prostatic leg that

“surpassed in elegance and utility previous models.” Known as the Palmer Leg, it was widely used

for disabled veterans of the Civil War.

After 1880, tannin

was replaced by chromium salts, which significantly reduced the processing time

and eliminated bark mills.

It was not uncommon

for a tanning mill owner to operate both

a bark mill and work as a shoe or harness maker. As early as 1815, Robert

Whitelaw of Ryegate operated a tannery on his farm at which he produced shoes

and boots. At one time, there were10

shoemakers in Ryegate, some of whom had shops with apprentices.

Others were both farmers and shoemakers. These part-time

shoemakers carried their kits from house to house, making and repairing boots

and shoes. After the middle of the 19th century, mechanized

processes began to replace individual craftsmen and shoemakers were relegated

to repairing footwear.

Leatherworkers also made harnesses, saddles, and horse

collars. They learned their trade working as apprentices for established harness

makers. John Buxton was a Newbury harness maker who took Ebenezer Stocker on as

an apprentice and later as a partner. Around 1886, Stocker accepted Henry Lowd

as a three-year apprentice. Completing

his apprenticeship, Lowd opened a harness business in Bradford and Newbury,

serving customers from Warren to Fairlee.

The Connecticut River was once the workplace of log-driving

river men. After 1810, local lumbermen

built rafts from boxes of logs, loaded them with area products, and floated

them down the river, returning on foot.

The first long-log drive from the great northern woods to

the mills in southern New England was held in 1868. Over the next 46 years,

this annual event represented the nation’s longest log drive. The drives began

when the ice went out.

Crews of hundreds of

men and horses guided millions of board feet of lumber through dangerous river

sections. The stretch from Fifteen Mile Falls north of McIndoe Falls to south

of Lyme and Thetford was one of the most hazardous in the 345 miles of the

river.

The most dangerous part of the drive for river men was when

jams occurred. With hundreds of logs

piled against each other like giant jackstraws, men had to pry them loose with

pikes and peaveys.

The men constantly risked their lives. They could easily be crushed in an avalanche

of loosened logs or sucked under by rapids. Those who lost their lives were

often buried in empty pork barrels.

By 1915, the northern forest had been harvested of long logs.

Drives of four-foot pulpwood continued until the 1940s. shortly before the

construction of hydroelectric dams.. The

rivermen on the Connecticut were no more.

In the 1850s, area farmers shifted from raising sheet to

having dairy cows. At first, the milk was used in the production of cheese and

butter. The number of farms in Vermont peaked in 1880 at 35,522. According to the 1888 Orange County

Gazetteer, the county has 3,400 farms with 13,072 dairy cows.

By 1900, half of the farms in Vermont and one-third of those

in New Hampshire had dairy as their largest “crop.” By the l920s a “river of

milk” flowed from dairy farms to eastern urban markets.

However, economic challenges, competition, and the increased

cost of production caused a steady decline in the number of small dairy farms.

As older farmers retired, younger men and women were unwilling to take on the

uncertainty and labor-intensive tasks of farming.

By 2009, Orange county had only 102 dairy farms and Grafton

county had about 40. It is estimated

that there are currently less than 600 dairy farms in Vermont and less than 100

in New Hampshire. There are still workers in the dairy industry, but their

numbers are a mere shadow of those of a century ago.

Ice harvesting was another industry impacted by new

technology. Before electric

refrigeration, ice was harvested from area rivers and lakes during winter and

stored in private or professional icehouses for later use. It was winter’s cash crop.

Accounts published in local newspapers documented this

annual activity. In January 1883, 20 men hauled ice for the Bradford Ice

Company to be sold throughout the area.

In 1896, Orford’s icehouses were filled with ice of “large quantities

and of most excellent quality” harvested from Lake Morey.

It was dangerous work. The equipment included sharp saws,

picks, and tongs. Heavy chunks of ice

were wrestled to the shore and into ice houses. There was always the danger of

men, horses and wagons breaking through the ice into the frigid water.

The expansion of electric home and business refrigerators

and electric milk coolers on area farms after 1930, reduced the market for ice.

It eliminated the need for both ice harvesters and the men who made home

deliveries.

From the 1840s to the

1960s, railroad station masters were the face of the railroad in each

community. They managed the depot, handled mailbags, sold tickets, operated the

telegraph, and were the freight and express agents.

When the railroad functions were replaced by motor vehicles,

railroads began to discontinue passenger and freight services. The Woodsville

passenger depot closed in 1960 and the stations at Bradford and Fairlee had

their last passenger train in 1965.

Two station masters stand out for their lengthy service. In

1914, Burnside Hooker moved to Bradford and became station master. He continued until his retirement in

1955.

During his years of service, he saw improvement in nearby

railroad bridges, signal systems, and the changes from steam- to diesel-powered

locomotives. Initially, the station

wagon that transported passengers to and from the station was horse-drawn. Hooker was highly respected and played a

significant role in Bradford town affairs.

Joseph Alger, Fairlee’s station master, played a similar

role. He took over the station in 1922 and continued until his retirement in

1957. Each summer, the station was especially busy with passengers and their

luggage bound for the area’s youth camps.

Alger’s interest in presenting a positive atmosphere at his

depot was recognized in the July 1949 Reader’s

Digest. An article described the well-kept Fairlee station as a “shining

example of what an energetic station agent can do.” Another national magazine article

drew attention to the attractive gardens he maintained immediately across the

tracks from the station.

Until the 1880s,

typesetters in the publishing industry set up copy one letter at a time,

selecting them from either upper or lower cases above their desks. An

advertisement for three female typesetters indicated that this was one

occupation open to women.

In the 1880s, this laborious technique was replaced by a hot

metal typesetting machine known as a linotype. This allowed one worker to perform

the labors of as many as six. News items

in Bradford’s United Opinion referred to both men and women workers.

In 1921 Caledonian-Record linotype operator Ruth

Impey set a Vermont record by producing six lines of copy per minute,

representing 7,000 letters in an hour. In 1929, Lolabel Allen (Hood) began

working as a linotype operator at the

United Opinion. Working beside male operators, she held the position until

the late 1930s.

In the 1970s, the linotype was replaced by compugraphic

typesetters and then by computers.

Journal Opinion publisher Michelle Sherburne recalls working on both of devices

to lay out copy.

Going back to the 19th century Orange and Grafton county

gazetteers, I found occupations listed that could have been included in this

article. Makers of brooms, gloves, ladders, bobbins, baskets, coffins, bricks,

paper, linen thread, and fishing rods are no lover as prevalent as they once

were.

Proprietors of livery stables, express offices, billiards

halls, creameries, grist mills and steamboats are also not as poplar. So too

are miners, penmanship teachers, and tailors as well as home deliverers of

coal, meat, and milk.

It is difficult to predict the occupations that will join

this list over the rest of this century. Undoubtedly, a significant number will

either disappear or be significantly altered by technological changes. If recent news reports are any indication, future

columns such as this one may be written by an AI program such as ChatGPT.

I can assure you this

one was not.

For a complete list of the 145 articles published in this column since 2007, go to the search block on the right side of page 1 and put in "list." It will appear at the top of page 2. To select any post, use the search feature again.

No comments:

Post a Comment