School Wagon: Contrary to stories that students had to walk to school uphill both ways, Bradford student had four horse-drawn school wagons in 1901. The one pictured delivered upper elementary and BA students to the Woods School Building on Main Street. (Bradford Historical Society)

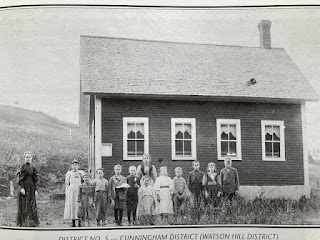

Little District Schoolhouse circa 1897. Built about 1883 at a cost "not to exceed $350," this one-room schoolhouse served Topsham's Cunningham or Watson Hill District. It was still in operation as late as 1911. The tall student in the white dress in the center of the front row is Nettie Wright (Pierson) the author's wife's grandmother. (Town of Topsham)

“Selectmen of towns to have a vigilant eye over their

neighbors, to see that none of them shall suffer so much barbarism in any of

their families as not to endeavor to teach their children and apprentices so

much learning as may enable them to read perfectly the English tongue.” NH

Provincial Legislature, June 14, 1642

Education was crucial in early New England as it enabled

people to read the Bible. By 1777 New Hampshire and Vermont required primary

schools in most towns.

In 1782, Rev. Gershom

Lyman spoke before the Vermont Legislature expressing, “the belief of the

majority of Vermonters when he referred to ignorance as ‘a natural source of

error, self-conceit and contracted, groveling sentiment.’”

Randolph Roth’s study of the early Connecticut River Valley

of Vermont found education in high regard. “Education promised to create an electorate

that would chose its representatives wisely.” Roth concluded that by the turn

of the 19th century, “the valley had one of the highest literacy rates in the

world, approximately 95 percent for men and 85 percent for women.”

That high rate of literacy was fostered at least until the

beginning of the 20th century in small, usually one-room, district schools. The

following includes just some local examples of this historic practice.

In local towns, such

as Bradford, Orford, and Corinth, the earliest schools were held in homes or

barns. In 1770, Orford voted to hire its

first schoolmaster. In 1773, Haverhill established its first primary school.

East Topsham built it first schoolhouse around 1810.

In 1782, Vermont

provided that towns could create neighborhood self-funding and self-governing

school districts. New Hampshire followed suit. Each district was “a little

independent commonwealth with certain defined boundaries.”

In local towns, the number of districts increased with

population growth, especially in previously unpopulated areas. Haverhill began

with 4 districts in 1786, added 5 more by 1815, eventually reaching 20. By the

early 1800s, Bradford was divided into 17 districts and several fractional districts.

The latter were districts that shared a school with adjoining towns.

The district was responsible for the construction of a

schoolhouse, usually within walking distance from most homes. Sometimes,

property for a new school was donated by a local landowner as property near the

school increased in value. Terms of up to 12 weeks were held 3 times a year,

with timing determined by farming practices.

Early schoolhouses lacked many of the amenities of later

schools. Initially, students sat on benches and, later, in straight-back desks.

At first, there were no blackboards, globes, or teaching supplies.

Student were expected to bring their own textbooks, which

often meant little uniformity in books. Students brought wood for the stove to

heat what were often cold, drafty buildings. Schools were without running water

for drinking or toilets.

Initially, only Vermont taxpayers who had school-age

children were expected to pay on a per-student basis. The early practice of

allowing taxes to be paid in labor or produce was abandoned and, by 1864, all

property owners were expected to pay school taxes.

A district school committee made decisions about school

operation., including securing a teacher, usually at the lowest possible price.

“The system was the occasion of more local quarrels than anything else in

town.”

In many local towns, the population peaked in the 1850s, and

Vermont schools had an average of 38 students. In 1860, there were 2,591 school

districts in Vermont with a reduced average of 29 scholars in grades 1-8. In

1867, Vermont required attendance for students up to 14 years of age. While

district students could stay beyond 16 years of age, few did. In 1854, New Hampshire had 2,294 district

schools.

As the population continued to decline in the latter half of

the 19th century, the average number of students also declined. In 1884, there were 103 Vermont district

schools with six or fewer students and 420 districts with between 6 and 11.

School were sometimes closed briefly until students were available or closed

permanently. Reduction in the number of

students in a district school did not result in a similar reduction in fixed expenses.

These factors led to a decline in the number of district

schools. In 1900, there were just over 1,500 district schools in Vermont, by

1920, there were 1,000, and by the 1950s, about 500. Abandoned school houses were often dismantled

or sold. By the beginning of the 21st century, the number of

one-room schools in the two states had dwindled to single digits.

This was especially pronounced in rural districts that

became underpopulated. The one-room school in Orford’s Quintown district is an

example. In 1894, there were only seven students, the following year, five, and

by 1900, it was abandoned.

Until the late 19th century, there were no state

certification requirements for teachers.

Generally, anyone who had completed the equivalent of high school could

be hired as a district school teacher.

While there were men hired as schoolmasters, most teachers were women.

In early Newbury, teachers received 50 cents a week.

Teachers were expected to board with families either on a weekly or full-term

basis. In some districts, the housing of the teacher was bid off to the lowest

bidder, which did not always provide the best of accommodations for the

educators..

This was the

description of one early Newbury teacher: “She was not incompetent, however,

having learned through her own efforts to read and write. She also knew a

little something of the science of numbers and taught successfully.”

The academic demands on teachers were significant. In 1867,

the teacher in the District 12 school in Bradford village taught 45 pupils 25

different subjects in an ungraded one-room school.

A good teacher was one who could keep order “even if

preserved with a rod.” Historian Steve Taylor described the discipline as

varying from “chaotic to dictatorial.”

During the winter term, big farm boys often created discipline

problems for younger teachers. Some

years ago, an elder told me of a local school that had a problem with a number

of boys who “broke up the school,” including driving teachers away. A new teacher arrived and, placed a large

whip over the blackboard, stating her intention to use it as necessary. She taught successfully for decades.

The district school was a center of local activity, and

school affairs were newsworthy. In February 1876, The United Opinion carried an

article on the “excellent and successful” winter term of West Fairlee’s

District 4 school. It had 27 students under the instruction of Miss Lydia

Smith,” an able and experienced teacher.”

Samuel Reed Hall opened the first teacher training or normal

school was opened in Concord, VT in 1823. He also operated a similar program in

Plymouth NH after 1837. Over the years that followed the Civil War, both states

operated normal schools that provided teacher training and increased

certification requirements.

Beginning in 1885, both states passed a series of acts

setting standards for school buildings, allowed women to vote in school affairs

and adopted a policy of town-wide graded school districts with consolidated

schools located in the centers of local population. In 1919, the NH state started a program to

improve underperforming schools.

In the late 19th century, both states began to reconsider

the self-financed neighborhood district.

In 1884, Vermont enacted a law encouraging towns to adopt the township system

of schools. Newbury voters voted twice not to adopt. In 1894, the state

mandated the town system. The takeover closed some district schools, whereas

other were kept and improved.

This town-wide control encouraged the consolidation of

schools. In 1895, Bradford built a new brick primary school on South Main and

placed grades 4 through 8 in the newly-constructed Woods School Building. These

locations served until a new elementary school was built in 1952 at which time

the last district school, located in Goshen, was closed.

In 1890-92, the Vermont Legislature passed legislation to

equalize school funding, improve teacher training, and consolidate school

administration. These efforts were

enhanced by further legislation in the 20th century.

A state-wide property tax, designed to use moved funds from

wealthier communities to assist poorer ones, passed with the support of rural

legislators. Their numbers were more influential because each town had one

representative, regardless of population. Orange County schools were among

those which benefited the most from this new tax.

That tax remained in effect until 1931. From then until it

was re-established in 1997, the cost of local education again depended on local

property taxes.

In 1892, hundreds of local Vermont school districts were

wiped out when the State replaced them with a single town-wide district. Known by its detractors as the Vicious Law,

this placed the responsibility for public education in the hands of a town

school committee.

As the district schools served a neighborhood, children who

lived within two miles walked to school.

As these local schools were discontinued, some town districts provided

school wagons. In 1902, Bradford students were transported in four school

wagons. Pulled by two horses, these canvas-covered wagons had two benches

running lengthwise.

On nice days, the canvas was rolled up. Often, boys had to

get out and walk up the steepest hills. In the Spring, all but the smallest

might be required to walk as the muddy roads became almost impassable.

Little Elizabeth Miller didn’t have to walk from her North

Road home to the West Newbury school because her family had the horse named Pete.

When Elizabeth started school around 1915, her family hitched Pete to a wagon

to transport her to school. After dropping his passenger off, Pete found his

own way home. Bradford’s Douglas Miller

recalled his mother’s story, adding that the afternoon trip didn’t work quite

so well. His mother had to walk home.

Newbury’s Aroline Putnam and Bradford’s Margaret Drew began

school in West Newbury in 1941 and recently spoke of those school days. They

said there were usually less than 30 students in the one-room school. Grace Whitman was the teacher and conducted

group lessons, sometimes with the help of older students. The school did not

have running water so, it was carried from a nearby farm. There were two

privies, one for boys and one for girls.

Drew agreed that it was

a “wonderful little school.” She recalled there were few discipline problems.

She remembered that sometimes boys would hop the tail of the milk truck to get

a ride to school.

In 1947, Putman, Drew, and the two other girls that made up

their class, transferred to the Newbury Central School. Whitman told them she

had taught them all she could. When

asked if she thought most children got a good education in a one-room setting,

Putman thought they did, but it “depended on the kids and their parents.” Having served the district for 75 years, the

school closed in 1970.

In some districts, one-room was replaced by two-room

buildings. East Haverhill resident Marilyn Seminerio recently related stories

of her experience in a two-room school in Chesterfield, NH in the years after

1935.

She said there were fewer than 25 students, but they were

divided into grades one through four and five through eight. Instruction was often ungraded, with courses

such as history and geography offered in alternate years. Her teacher heated

soup on the top of the wood stove for those students who could not walk home

for lunch.

How communities handled the consolidation of their

elementary schools varied. Where there

were several village centers, separate schools existed longer. Wells River maintained a separate school

system long after the rest of Newbury consolidated.

When Thetford’s new elementary school opened in 1962, it

replaced district schools in Union Village, North Thetford, East Thetford, Post

Mills, Rice’s Mills, and the Stevens District.

Several village

schools were maintained in Corinth and Topsham until Union 36 opened in 1972.

In 1898, a new two-story Orfordville School was built to

accommodate students as many of the town’s district school were phased

out. In 1901, Fairlee voted to build a

new two-story building at the south end of the village. This was used as the elementary school until

a new building was built in 1956.

These are just examples of the continued consolidation of

school districts. Since the 1960s, town school districts have merged in a

number of configurations.

Those interested in the further history of the one-room

district schools that once operated in their neighborhood are encouraged to go

to their town’s history book. Most have extensive descriptions. My article on

the early history of area high schools can be found on my blog at

larrycoffin.blogspot.com. It is entitled School Bells: Academies &

Seminaries 1790s-1890s.

CAPTIONS: