Journal Opinion Jan 26, 2022.

From corporal punishment to intentional neglect, children

are too often subject to cruelty.

This column reviews child abuse and intentional neglect

before 1930. Included is information from New Hampshire and Vermont history,

using examples from vintage newspapers and online sources. Newspapers usually

covered only the most egregious cases. Early local historians did not mention

these issues.

This column does not cover the typical interactions between

adults and children that result in mild punishment. A swat with an open hand, depriving a child

of a desired pleasure, or sending a child to bed without supper are not the

type of examples covered. Parents are not given a manual of instruction when

given the care of children, especially when dealing with a willful child.

Instead, it deals with examples of ongoing physical or

emotional abuses. History recognizes that some adults are not fit emotionally,

physically, or psychologically to be in charge of children and take advantage

of their vulnerability.

These abuses are sometimes perpetrated by an adult who, when

intoxicated or incensed, becomes a brute. In that case, the switch, belt, or

fist becomes a weapon. It often occurs when the perpetrator is not the natural

parent of the child involved.

Until the latter part of the 19th century, children were

their father’s property. Even though the government had the ultimate role of

protecting children, it rarely restricted household authority.

Parents were expected to raise children with a moral

character and a strong work ethic. “Spare the rod and spoil the child” was the

rule. Disobedient children, it was thought, needed to have “the devil beaten

out of them.” Local governments were more likely to remove children from a

family that did not provide the proper life lessons than one that physically

abused them.

Craftsmen frequently took boys as young as eight as

apprentices. Girls were assigned to families to learn housekeeping. Apprentices

were often orphans or children abandoned by their natural families. Their

treatment varied from caring to cruel. Local governments did intervene in

severe abuse or neglect cases and would assign the child to a new master.

Frequently, children

who were adopted as orphans or lived with stepparents were vulnerable to abuse.

In 1831, a New Hampshire minister beat his adopted son almost to death when the

child had difficulty pronouncing difficult words. This is an example of some

adults’ lack of understanding of child development.

If physical or emotional abuse was secretive, sexual abuse

of children was even more so. Authorities

were unwilling to admit that it could even possibly exist. Not until the

1920s was the study of child molestation recognized. The practice of allowing

older men to marry girls as young as 13 sometimes circumvented charges of

abuse.

Local governments often placed orphans or neglected children

with other families, often without ongoing supervision or consideration given

to the child itself. Corinth was one

town that “bid off” such individuals to the lowest bidder. That bidder was supposed

to provide necessities, but that was sometimes not the case.

In the early 1800s,

Corinth bid off the two children of Jonas Taplin who could not care for them.

Tragically, the two children were locked by their caretaker in an unheated shed

where they died of starvation and exposure.

Children orphaned or taken from families were sometimes

placed in the town poor farm by the Overseer of the Poor. The discipline there

was often harsh with whipping and solitary confinement used.

Private and public orphanages were created in both states in

mid-19th century. Many “orphans” actually had one or both parents unable to

care for them. Many children were placed in orphanages for just short periods.

Discipline was described as rigid. The rise of foster care in the late 19th

century caused children to be “placed out,” often as workers.

Early orphan asylums in the two states included the St.

Joseph’s Orphanage (1854) and the Home for Destitute Children (1866), both in

Burlington. The Orphans Home and School for Industry in Franklin, NH, and

Spaulding Youth Center of Northfield, NH, were both opened in 1871. Given

recent charges of abuse in institutions such as these, perhaps these abuses were

systematic.

After the Civil War, two cases highlighted the abuse of

children. In 1869, Samuel Fletcher, a blind youngster from Illinois, was locked

in a cellar by his parents. When he escaped and reported the abuse, his parents

were fined $300 in one of the first court rulings recognizing children’s right

to be protected against abuse.

In 1866, Mary Ellen Wilson of New York was placed in a

foster home with Francis and Mary McCormack. Over the next several years, the

youngster was severely physically abused, malnourished, and neglected. The

widely publicized trial of the McCormacks led to the establishment of the New

York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, the first such

organization.

The following abuse cases were reported in Vermont

newspapers. While neighbors often declined to intervene, concerned neighbors

eventually led authorities to investigate. In some cases, the perpetrator’s

punishment did not seem appropriate to the crime.

In 1879, 9-year old Alice Meaker of Duxbury was sent to live

with her half-brother. Over the next

year, his wife Emeline severely abused the child. In 1880, Emeline and her son

Almon poisoned the child. Both were found guilty of murder. Both died in

Windsor state prison.

In 1906, a Vershire man took charge of a 9-year old boy from

the Children’s home in Burlington. He

was charged with cruelty after the horrible treatment of the youngster. The

child was forced to work in the woods for long hours, was ill-clothed, and

forced to sleep in an unheated attic.

In 1913, a Waterbury man was imprisoned in Windsor Prison

for whipping a little child.

In 1915, a Brattleboro woman was fined $10 for publically

assaulting a child of eight with a whip, leaving marks on her legs.

In 1919, a well-known farmer from Walden was tried for

breach of peace for whipping a 12-year old disabled orphan in his charge. After

a highly publicized trial, he was found guilty and fined $50 and costs.

Underage runaways experienced abuse or neglect. This was

sometimes due to harsh work conditions. The number usually increased during

tough economic times. On the street, underage runaways and homeless children

were especially vulnerable.

Several examples of runaways that received newspaper notice

included an offering of a five cent reward for information on a 14-year old

apprentice from Sherburn, VT who ran away from his master in 1836.

Then there is the story of Charlotte Parkhurst. She was born in Sharon in 1812 and, after the

death of her mother, was placed in a foster home, perhaps in Lebanon. She ran away, adopted a masculine identity,

became known as Charley, and became one of the top stagecoach drivers on the

West Coast.

Articles mentioned runaways from the State Reform School in

Waterbury and the State School for the Feeble Minded in Brandon. The latter led

to charges of abuse. In 1921, a 15-year

old lad from Wells River ran away from home after “a sound thrashing.”

The number of children who ran away from home varied with

economic conditions. The number significantly increased during the economic

depressions. On the street, underage runaways were especially vulnerable.

Juvenile offenders were another group of youngsters who

faced abuse or neglect. This was especially true when they were incarcerated in

prisons, jails, or workhouses. In the 1850s, officials in both New Hampshire

and Vermont raised concerns about the imprisonment of children “confined with

hackneyed and callous malefactors.”

In 1852, New Hampshire established a state reform school in

Manchester, and in 1865, Vermont opened one in Waterbury. In 1912, Vermont began to deal with youthful

offenders in a juvenile court system.

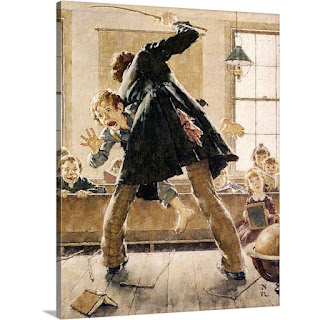

A history of early New Hampshire schools recalls severe

abuse by schoolmasters. The frequent use of rods and ferules left “blistered

hands, swollen ears, and smarting limbs.”

A ferule was a flat ruler used to punish children. The History of

Canaan, NH, mentioned: “most children got whipped every day, either at home or

at school, sometimes at both.”

“Faced with reckless wretches,” a Vermont teacher in 1845

felt that “rough means became fair.” Many teachers felt there was “an

irresistible persuasiveness” in applying the ruler.

Born in 1810, Eliza White Root recalled abuse in Burlington

schools. “I thought the teacher very cruel, as he would often ferule the boys,

gag them and make them stand and hold their arms upright.” Parents generally

accepted corporal punishment, and sometimes, a second at-home punishment

followed.

“Good order is the

jewel of the schoolroom” wrote one editor. He criticized those parents who

threatened a teacher who applied the rod to their child and further blamed them

when they could not control their children at home but expected the teacher to

manage a whole classroom of children.

Often corporal punishment became actual abuse when the adult

involved allowed emotions to overwhelm the situation. In 1867, a Springfield

teacher applied a rawhide whip to an 11-year old boy. Described as an

“outrageous child,” his body was bruised and discolored.

In 1883, a suit was brought against a Pittsfield teacher who

thrashed a boy. “The jury decided she did the proper thing.” A few years later,

an article on why female teachers should be paid less included: A male teacher

“can trash an unruly boy into obedience, she can’t.”

There was a belief that corporal punishment was not only

necessary but had a lasting positive impact.

In 1875, the Vermont Phoenix carried the following: “The birch rod, too,

has much to do with our public schools, and most of our great men have been

soundly thrashed with it while boys.” In 1914, that attitude continued: “A good

thrashing has saved many a boy,” making “them a better man.”

While naughty boys might be physically punished, girls were

more likely to be just reprimanded. A

West Randolph newspaper suggested that boys preferred a trashing to a

girly punishment such as standing in the corner.

Schoolroom discipline in the decades that followed was

“abrupt and absolute.” Paddles gave new

meaning to the term “board of education.”

Sometimes being sent to the Principal’s office resulted in more of the

same.

In 1867, New Jersey was the first state to prohibit corporal

punishment in schools, but it was more than one hundred years before another

state would follow. In 1974, federal legislation required states to establish

child abuse reporting procedures and investigation systems. New Hampshire and Vermont took steps to

implement these requirements.

There were changes in attitudes toward corporal punishment

from 1880 to 1920. Adults in charge of children were advised to avoid

chastisement when hot-tempered. In 1895, an article in Bradford’s United

Opinion suggested, “While with a firm hand you administer parental discipline,

also administer it very gently.” In 1909, the newspaper further suggested,

“Think twice before raising your hand to hit a child.”

With industrialization in the 19th century, there was

concern over the employment of children in mills and factories. Children were

often employed to supplement family income. Many believed that it was morally

desirable for children to be employed rather than “lazy or wild.” Employers often wanted children for their

lower wages and because their small size was sometimes an advantage, something

that labor unions disputed.

The woolen industry in both states employed young children.

The Winooski Woolen Factory employed some children under the age of 12 at low

wages and for workdays of up to 14 hours.

In 1867, Vermont was the last New England state to limit the

number of hours children could work in factories. But these early laws only

applied to children under 12. There were cases where these laws or the school

attendance requirements were ignored. In 1911, the Vermont Child Labor

Committee was established to combat child labor exploitation.

At the turn of the 20th century, the child-saving movement

included the creation of child protection societies. The New Hampshire

Children’s Aid and Protection Society was formed in 1914 to deal with child

abuse and neglect in that state. Vermont’s Children’s Aid Society was

established in 1919 with a special charge to deal with the problems of children

orphaned by the Spanish flu epidemic.

While laws have been changed to protect endangered children,

for some, this is still a hidden family secret. Professionals are required to

report suspected cases. Neighbors who notice abuse and neglect are under no

legal obligation to report but may report anyway. We can only hope that the cry of the abused

will be heard by those who can answer it.