Eighty years ago this month a series of floods set records

for high water in the Connecticut River Valley, throughout New England and a

major portion of the eastern United States. This article deals with the impact

of those floods.

The winter of 1935-36 created the conditions that led to the

floods that followed. Across New England there was an above-average snowpack

with high water content, heavy ice cover on rivers and deep penetration of

frost. David Ludlum writes in The Vermont

Weather Book: “A great mass of frozen precipitation was stored on the hills

and mountains awaiting spring conditions that would be its release to start

downhill on the long journey to the sea.”

During the middle of March 1936 the Northeast experienced a

series of storm systems. Each moved from the Gulf of Mexico, eventually

bringing heavy warm rainfall and rapidly rising temperatures to Vermont and New

Hampshire.

Ludlum reports that in the first major storm of March 11-12

over six inches of rain fell in northern New Hampshire and four inches fell in

southern Vermont in a 24-hour period. During the second major storm, heavy rain

fell over Northern New England on every day from March 16 to 22. Wide areas of

the region received between 10 inches and 30 inches of rainfall.

The warm air and rainfall caused the ice-clogged waterways

to breakup and flow downstream. The snowmelt added a tremendous volume of water

to the ice-clogged rivers and streams. Ice jams acted as dams and backed up

water caused significant flooding.

The United Opinion

covered the local flooding in great detail. The headline for the March 20th

edition read “Bradford is Practically Isolated from Outside World for Four

Days.” Coincidentally, that edition included the first chapter of the romance novel

“Storm Music” by Dornford Yates.

The following description includes material from the newspaper along with accounts from other sources. During Wednesday night March 11 it rained. Typical of the entire area, Fairlee village residents were kept awake by the rainfall and “the men were kept busy turning water to keep it out of cellars.”

The following description includes material from the newspaper along with accounts from other sources. During Wednesday night March 11 it rained. Typical of the entire area, Fairlee village residents were kept awake by the rainfall and “the men were kept busy turning water to keep it out of cellars.”

It rained all day on Thursday March 12, “causing the Waits

River and its tributaries to swell and sent out vast amounts of ice in

monstrous ragged cakes.” The railroad tracks were washed away at Pompanoosuc Station

between Norwich and East Thetford, discontinuing all freight and mail trains.

A

work train was stationed in Ely to provide support for the crews working to

repair the wash outs on the roadbed all along the system.

The Bradford golf course was completely inundated and by

Saturday the water had, wrote one columnist, “spread out into a beautiful lake

many of us wish was a permanent feature for our little town.”

Sightseers on Sunday came to view the lake. Some found Route 25 jammed with ice. Others traveled to East Barre whee another lake spread from the flood control dam to the base of Orange Heights. That dam, built following the Flood of 1927, protected Barre and Montpelier from the major damage they had previously experienced.

On Monday the 16th, “torrents of rain” fell and

continued through the night. By Tuesday night the roads south and north from

Bradford village were closed to traffic, along with the road to Piermont. The

water came up 5 feet during the night and the lake formed by the flooding Waits

and Connecticut Rivers was dotted with ice flows and debris.

The Bradford railroad station was surrounded by water and trains

that had begun to get through were again stopped by submerged tracks. The local

grain facility lost over 60 tons of grain and cement. North Thetford village

was flooded with “much damage” to homes and some residents had to be rescued by

boat.

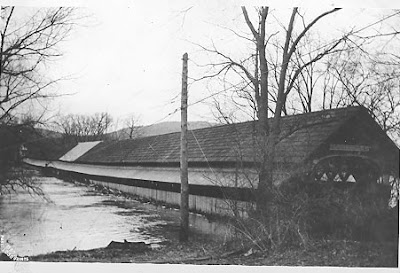

Between Tuesday night and

Wednesday, the Piermont, Orford and two Thetford bridges were closed as a

result of the danger. An ice jam at Newbury broke sending quantities of ice,

water, logs and other debris against those structures. Loads of sand was used

to prevent the bridges from floating away.

The railroad bridge in Woodsville was weighted

down with carloads of cinders. One span of the East Thetford bridge was lost

and the Orford-Fairlee covered bridge was damaged beyond repair.

When the dams at 15-mile Falls and North Stratford, New Hampshire

were either open or breached more water flooded into the already over-burdened

Connecticut, flooding towns to the south. The middle sections of Jackman and

Page dams in East Corinth went out, adding to the flood on the road to

Bradford.

By Wednesday night, March 18th, many communities were

isolated with all roads closed. The rising water flooded the power station at

the Bradford falls and electricity was cut off. Sections of Newbury, Piermont

and Haverhill, especially Woodsville and areas along rivers, were also isolated

and without electricity

“Thursday morning brought a cold leaden sky which over

looked a desolate waste of water which had risen rapidly during the darkness.”

At that point the level was two feet higher than that of the flood of 1927. The

water “lapped” at the back of the buildings along the east side of Bradford’s

main street.

About 3:30 Thursday afternoon, rain began to fall again. By

Friday morning, March 20, the rain had been replaced by the sun “shining in a

half hearted manner.” It was on that day that the flooding reached its highest

level, about five feet above the 1927 mark. Someone painted a line on the

furnace building of the Bradford Academy to make note of that March 20th

high water level. It still can be seen there and has never been surpassed.

By Saturday the water began to recede and continued to do so

over the next few days. The newspaper reported stories of rescues from the

previous week of both individuals and livestock. Stories of boats being used to

get milk to dairies, voters to meetings and some students to the schools that

remained open were also reported. Fairlee students who attended Orford High

School were kept out of school until a temporary bridge could be built.

During the flood,

Norris’s store in Woodville received supplies from Littleton via a trolley

across the Wild Ammonossuc. Lyme physician Dr. William Putnam opened an office

at Thetford Academy and had a car on each side of the river while the East

Thetford Bridge was being repaired.

Much credit was given to the Central Vermont Public Service

crew who “came through in style,” restoring electricity. In several cases they worked from boats on

wires suspended over floodwaters.

Whatever damage and

inconvenience suffered locally was small when compared to that experienced

elsewhere across the northeastern half of the nation. From Virginia and Ohio through northern New

England the great flood of 1936 inundated communities. Rivers from the

Mississippi to the Monongahela in the Midwest to the Kennebec and Saco in New

England flooded. In many places high water broke records going back several

centuries.

In New Hampshire, the Merrimack flooded Manchester and

Nashua and went on to flood the Massachusetts communities to the south. Over 87 towns and cities in New Hampshire

suffered flood damage.

Along the entire length of the Connecticut River new flow

records were established. As small

rivers and streams added to the rainfall, the impact was magnified downstream.

At Bellows Falls 29 feet of water flooded over the top of the dam. North of the

Vernon dam a six-mile ice jam broke submerging the top of the dam by nearly 11

feet and flooding the communities below.

By March 19th

50,000 residents of the lower Connecticut River valley were homeless. Springfield,

Massachusetts and Hartford, Connecticut were inundated in the worst flooding in

history. Up to 200 lives were lost in

New England and property damage was over $100 million.

The floods significantly increased the demand for flood

control and virtually assured the passage of some sort of national flood

control legislation by the federal government.

Even as the Roosevelt administration was dispatching a force of 275,000

relief workers to the devastated areas of the Northeast, efforts were being

made to push through a gigantic flood control bill.

An editorial in The

United Opinion in April, 1936 summarized the need: “All New England now

feels that something permanent must be done to prevent disastrous spring

floods…Southern New England now realizes that reservoirs nearer the headwaters

of the rivers is their best protection since flood waters are no respectors

(sic) of state lines… It is an expensive program but more than worth its cost

in the end.”

There had been federal flood control legislation and dam

building projects before. The Comerford Dam in North Monroe , built between

1928 and 1930 was, like many, primarily for hydroelectric power. Conversely, the East Barre dam was built by

CCC workers in 1933-1935 as a flood control reservoir.

The new proposal differed in significant ways. By establishing a major commitment to

protecting people and property from flood, it changed the role of the federal

government. It expanded the role of dams to include reservoirs for flood

control. The Army Corps of Engineers was also given greater responsibility for

dam flood control construction and operation.

There had been earlier opposition to flood control projects

from conservatives over this expanded role of the national government, the lack

of revenue and the impact that dam construction might have on private property.

That opposition virtually disappeared in the wake of the 1936 floods.

On June 22, 1936 President Roosevelt signed the Flood

Control Act of 1936 into law. In later

years, it would be followed by other legislation complimenting and expanding

the federal government’s role in flood control.

Between 1941 and 1961 the Army Corps constructed seven flood

control dam with the capacity to control a portion of the runoff from the upper

Connecticut River watershed. The Union Village Dam and the North Hartland Dam

are two of those. The Corps also works

with hydroelectric dam operators and private landowners to try to contain

recurring floods.

One provision of the 1936 legislation allowed states to

enter into compacts involving flood control. Such agreements have been reached between

Massachusetts and Connecticut and Vermont and New Hampshire to compensate the

two northern states for the costs of protecting the two southern states.

The 1854 wooden covered bridge between Orford and Fairlee

was damaged beyond repair and was dynamite.

In June 1937, a new bridge was dedicated. Built for $209,000, it was named The Samuel

Morey Memorial Bridge. A new two-span bridge was built in 1937 between East

Thetford and Lyme to replace the damaged 1896 bridge.

Despite the changes in federal policy toward flood control,

opposition to dam and reservoir construction continued. Republican George Aiken

led the opposition to the enhanced Federal role in dam construction as a member

of the Vermont legislature and as governor.

In 1938, Vermont U.

S. Senator Warren Austin wrote in a private letter “We are in a great fight

over the New Deal flood control bill which would give the Federal Government

power to seize more for dams and reservoirs, driving the inhabitants out,

tearing up roads, etc. We know we are licked, but we fight on.” There was similar opposition when the new

Wilder Dam was proposed in the 1940’s.

For centuries there have been major floods on the Connecticut

River. Major ones between European settlement and 1936 include those in 1770,

1862, 1913 and 1927. Some of those caused greater damage than the 1936 flood.

One example of this was the major destruction to Wells River village in 1927.

There have major floods since 1936, including 1952, 1960,

1973, 1996 and 2011. In some towns there was greater damage and higher flood

levels than 1936, while other communities were spared. Much of the local area was spared the damage

from Tropical Storm Irene that so devastated other parts of Vermont.

For centuries little children have chanted the nursery rhyme

“Rain, rain go away. Come again some other day.” One thing is certain: for

those of us who live in the Connecticut River watershed, that “other day” is

sure to come and so will rain and, ever so often, floods.